When cooking with shrimp it’s easy to view the shell as simply an impediment to accessing the sweet, briny flesh inside.

For the Shrimpiest Shrimp Stock, Cook the Shells for Just 5 Minutes

Published Mar. 31, 2023.

The wide availability of peeled shrimp suggests many cooks avoid dealing with it altogether. But to overlook these crustaceans’ exoskeletons is to take a pass on a considerable amount of flavor.

Shrimp shells are loaded with flavor compounds that can actually be passed on to the flesh during cooking, which is why we often prefer to cook shrimp shell-on.

In fact, the shells are such a trove of flavor, they can be the foundation for a surprisingly shrimpy-tasting stock. All you need to do is brown them (which develops savory Maillard flavors as well as a bounty of subtle seafood aromas) and simmer them in water with a few seasonings.

However, unlike chicken broth or beef broth, where long cooking extracts more flavor out of the bones and scraps, simmering shrimp shells for longer does not improve the stock. In fact, it can make it taste more bland.

The compounds associated with shrimp flavor are highly volatile, so a short simmer is actually better. How short? Five minutes.

Sign up for the Cook's Insider newsletter

The latest recipes, tips, and tricks, plus behind-the-scenes stories from the Cook's Illustrated team.

We designed an experiment for simmering shrimp shells to nail down this specific timing.

Comparing Cook Times for Shrimp Stock

We simmered batches of shrimp shells (each batch contained the shells from 1½ pounds of large shrimp, or 4 ounces of shells) in 1½ cups of water, covered, for 5, 10, 15, and 30 minutes.

After simmering, we strained the broth. To eliminate the chance that any flavor concentration resulted from evaporation, we added water back into the longer-cooked samples so that all samples were the same volume.

Samples were tasted warm (160 degrees) and tasters were asked to comment on the intensity of the shrimp flavor of each sample. We repeated the test three times, each time with a different set of tasters.

The Winner?

To our surprise, tasters almost unanimously chose the 5- and 10-minute simmered samples as “more potent,” “shrimpier,” and “more aromatic” than the 15- and 30-minute simmered samples.

By analyzing the rankings from each round of testing we found an inverse relationship between cooking time and shrimp flavor intensity.

Why Simmering Shrimp Shells Longer Isn’t Better

Some savory compounds found in shrimp shells, such as glutamic acid and the free nucleotide inosine monophosphate (IMP), are nonvolatile and stay in the stock, rather than releasing into the atmosphere.

But our experiment showed that the compounds that we associate with shrimp flavor are highly volatile.

Shrimp shells contain polyunsaturated fatty acids that quickly oxidize during cooking into low-molecular-weight aldehydes, alcohols, and ketones. These low-molecular-weight molecules rapidly release into the air, providing a pleasant aroma during cooking but leaving behind a bland broth.

So to get the most out of your shrimp shells in a stock, keep the simmering time to just 5 minutes.

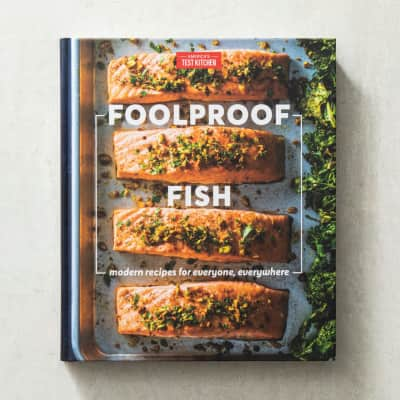

Foolproof Fish

Want to broaden your seafood scope? No matter what you buy from the fish counter, this award-winning book will teach you how to cook it.How to Make Simple Shrimp Stock

Never discard your shrimp shells. Freeze them to make stock whenever the need arises.

Heat 1 tablespoon vegetable oil in Dutch oven over high heat until shimmering. Add shells from 1 pound shrimp and cook, stirring frequently, until shells begin to turn spotty brown, 2 to 4 minutes. Add 4 cups water, 8 black peppercorns, 1 bay leaf, and ½ teaspoon salt and bring to boil. Reduce heat to low and simmer for 5 minutes. Strain stock through fine-mesh strainer set over large bowl, pressing on solids with rubber spatula to extract as much liquid as possible; discard solids.

Uses for Shrimp Stock

Shrimp stock can enhance the seafoody flavor of any number of applications. Use it in soups and stews calling for fish stock or clam juice, such as moqueca or cataplana, or in pasta dishes like linguine allo scoglio. In our Shrimp Scampi and Shrimp Risotto, we call for shell-on shrimp and turn the shells into stock as part of the recipe, making sure to simmer them for just 5 minutes.