My Goals

- Medium-rare interior from edge to edge

- Thick, well-browned crust

- Minimal splatter or smoke

Published May 1, 2007.

I was convinced that there was a better way to cook thick steaks, a new method that would give them the tender treatment they deserve.

Cooking a standard supermarket steak is easy—we’ve been doing it for years; just get an oiled pan smoking hot and slap in your steak. A flip and a quick rest before serving, and you have dinner. But try this method with a thick-cut strip steak (I’m talking almost as thick as it is wide) and you run into some problems. By the time a good crust has developed and the very center of the steak has reached medium-rare (130 degrees), the bulk of the meat is dry and gray. I was convinced that there was a better way to cook thick steaks, a new method that would give them the tender treatment they deserve.

To begin, I had to figure out what was causing my meat to turn gray. When beef reaches temperatures above 140 degrees, it undergoes structural and chemical changes that cause it to dry out and toughen, as well as lose its red color. I wanted to keep as much of the meat under this critical temperature as possible. However, the Maillard reaction (which is responsible for the deep color and rich meaty flavor of a well-browned crust) occurs at temperatures closer to 300 degrees. The ideal technique would have to entail quickly searing the exterior to develop a crust while slowly cooking the interior to allow for more even heat distribution. My job was to reconcile these two conflicting goals.

My first attempt was using a technique proposed by food scientist and writer Harold McGee: By flipping the meat as often as once every 15 seconds, the heat will diffuse gradually through it, resulting in a steak that’s cooked more evenly. This method did provide a uniform crust and a fairly evenly cooked interior, but to cook four steaks at a time, I had to flip one about every four seconds. With the 176 flips required over the course of the 11-minute cooking time, I’d flipped the equivalent of 88 pounds of meat—maybe doable for a short-order cook on steroids, but not for your average home cook.

Traditional way (left): By the time thick steaks come up to temperature in the middle, a wide band of dry, gray meat has developed below the crust.

Our method (right): Our method starts the steaks in a low oven to gently raise their temperature. The rosy interior extends nearly to the crust.

Next I tried pan-roasting, which involves searing the steaks in a hot pan, then transferring them—pan and all—to a blazing 450-degree oven to quickly finish cooking. This resulted in the familiar gray band and chewy meat. I wanted my steaks to finish cooking more gently, so the next time around I transferred them out of the hot pan and onto a rack and lowered the oven temperature to a mild 275 degrees. Thirty-two minutes later, the steaks were noticeably more tender in the center—due to increased enzymatic action—but still had 1⁄4-inch-thick gray zones around their perimeters.

Our steaks spend a long time in a warm oven, yet taste more tender than traditionally prepared steaks, which can be tough and chewy. The explanation? Meat contains active enzymes called cathepsins, which break down connective tissues over time, increasing tenderness (a fact that is demonstrated to great effect in dry-aged meat). As the temperature of the meat rises, these enzymes work faster and faster until they reach 122 degrees, where all action stops. While our steaks are slowly heating up, the cathepsins are working overtime, in effect “aging” and tenderizing our steaks within half an hour. When steaks are cooked by conventional methods, their final temperature is reached much more rapidly, denying the cathepsins the time they need to properly do their job.

Comparing cross-sections of a steak at different cooking stages revealed that this gray band was created during the initial browning. It seemed that a low oven was the path to tender meat, but I needed to speed up the searing process so that the meat just underneath the surface would not have time to overcook.

It struck me: To get well-browned, juicy steaks, start with dry meat.

Basic thermodynamics: When a 40-degree steak is placed in a 400-degree pan, the temperature of the pan drops significantly. Until it reheats to 300 degrees, no browning can take place. A cold, thick steak added to a hot pan can take upward of 4 minutes per side to form a good crust— during which time the meat beneath the surface is overcooking. Preheating the pan longer and with more oil only sent my hopes up in flames. But what if I upped the starting temperature of the meat? I put the steaks in a zipper-lock bag and submerged them in 120-degree tap water; 30 minutes later, they had reached 100 degrees. Convinced that this was the solution, I transferred the warmed steaks to a preheated pan—where, alas, it still took more than 6 minutes to brown both sides properly.

While racking my gray matter, I recalled a grade school science experiment. A paper cup full of water was placed directly over the flame of a candle, yet the paper did not burn. The cup was left over the flame until all the water had boiled away, at which point the cup finally ignited. Turned out that as long as there was still water in the cup, all the heat from the candle was being used to boil and vaporize the water, preventing the cup from ever going above 212 degrees (the boiling point of water). My point? Just as a paper cup can’t burn if there is any water in it, a steak can’t brown until all of its surface moisture has evaporated.

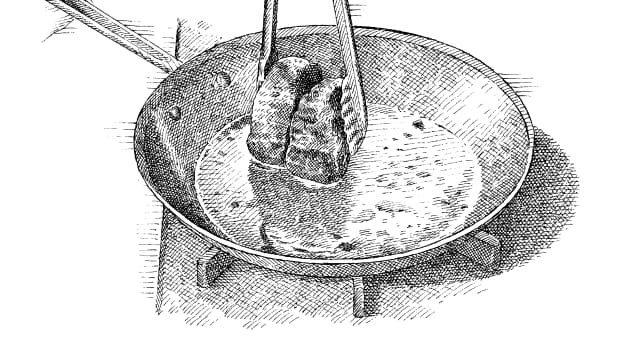

Taking Sides

Use tongs to sear the sides of two steaks at a time.

That explained my failed zipper-lock bag test. The moisture that was sweating out of the warming steaks was coming into direct contact with the pan, thereby reducing the rate at which it could heat up. It struck me: To get well- browned, juicy steaks, start with dry meat. I seasoned some steaks as usual, this time moving them straight from the fridge into a 275-degree oven. After 25 minutes, they had warmed to 95 degrees and the surfaces looked like desiccated lunar landscapes. I began to doubt my theory, but then I seared them; they developed beautiful brown crusts in less than 4 minutes. I held my breath while they rested. As the knife cut through the crispy crust, it revealed pink, juicy, tender meat—the gray zone was all but gone.

Medium-rare interior from edge to edge

We gently warm the steaks to 95 degrees in a 275-degree oven and then sear them just before serving. Because most of the cooking is quite gentle, the meat is perfectly cooked, even right under the crust.

Thick, well-browned crust

We maximize flavor by searing the precooked steaks quickly in a hot skillet. Once the flat sides are browned, we use a pair of tongs to hold two steaks at a time to sear their edges.

Minimal splatter or smoke

There’s less smoke and a lot less splattering because the oven dehydrates the exterior of each steak (it’s the water that causes all the mess).

This is a members' feature.